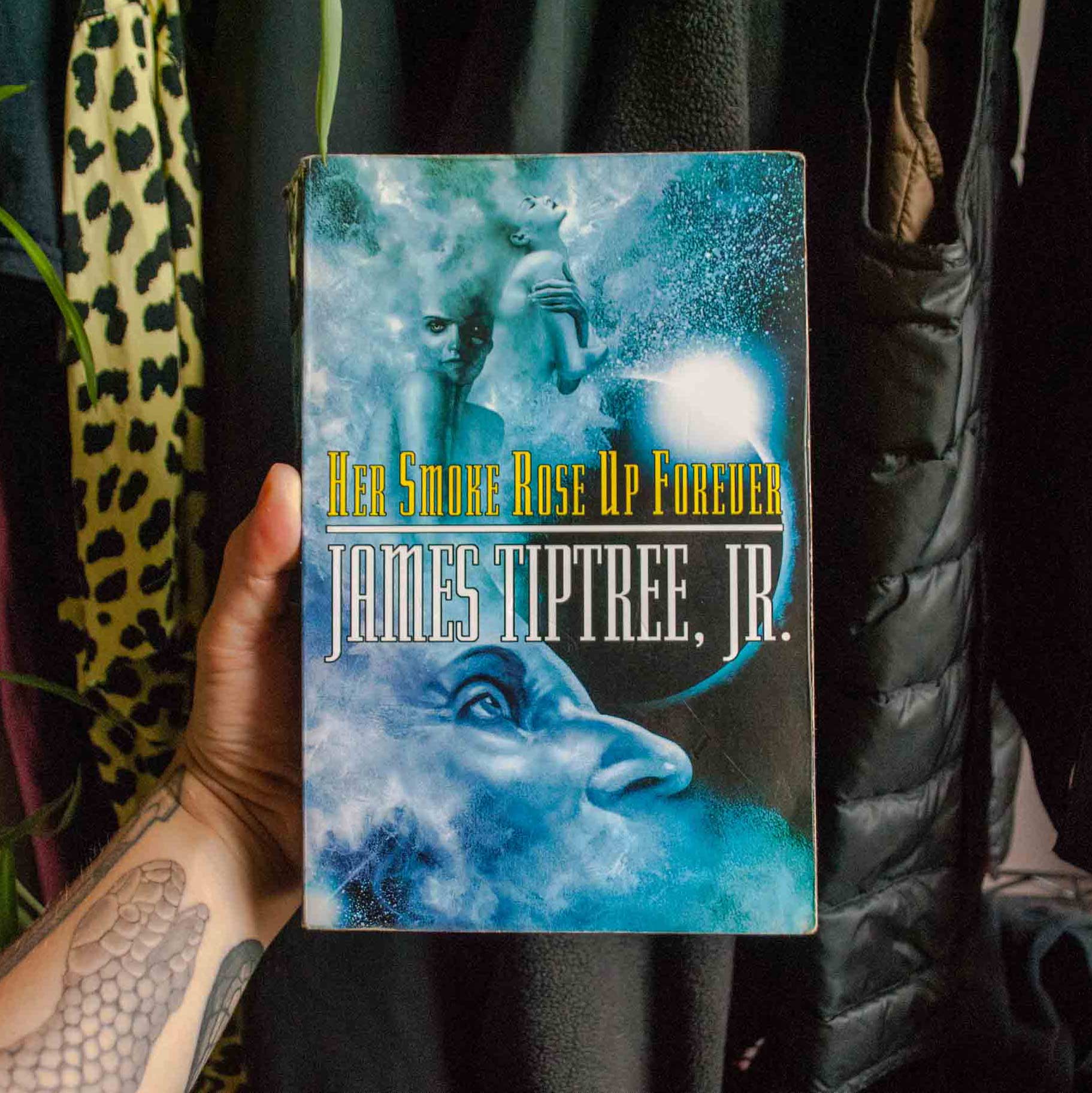

A brutal meditation in a hefty short story collection. Tiptree wrote dark and fatalistic sci-fi that lingers on today as something of a passed over and forgotten writer of the 70s speculative and feminist sci-fi waves (well this book is still in print so it’s not that forgotten). At one point Tiptree was lauded as one of the rising greats alongside Philip K. Dick, and then that all changed once the author’s “real” identity was outed by an invasive fan.

With a ‘male’ author’s name and minimal backstory as to who they were, the subject matter of Tiptree’s stories probably don’t seem relevant to readers of 2020. Tiptree’s contemporaries and torch bearers––seemingly all cisgender people––continue to speak of them as a woman writer who found success under a male pseudonym. And that is really fucking sad to me because I feel Tiptree was trans and it’s obvious. I think it’s extra sad because there is a literary prize named after Tiptree (or was) awarded to works that explore gender… Ugh.

My suggestion: Read this book back to back with Julie Philips biography, James Tiptree Jr: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon and your time with these short stories will be greatly enriched.

The short stories read as scathing critiques on mid 20th century gendered violence and patriarchy, set in outer space, future Earth and other worlds, and built around recurring themes of women as invisible, alien, or having their agency controlled by an imbecilic male protagonist who does not realize women are people. It’s worth noting that the protagonists are overwhelmingly men and the women in these stories are seen through their eyes––their bodies and their (irrational foolish girlish hysterical) behaviors especially. To me, these portrayals come off as caustic critiques of white male entitlement and violence.

Content warning for sexual violence:

A fair number of their stories involve direct scenes or implications of sexual coercion and sometimes rape. I read this book while I was in talk therapy to deal with anger and repression from sexual trauma myself, and the expression of intrinsic atmospheres of violence in these stories made me extremely sensitive and spooked towards men in my surroundings for the duration of my read. The sexual violence is often something that simply happens and then the story moves on (as opposed to being a catalyst for female revenge or some such trope), and very much feels as real and disruptive and mundane as sexual violence IS. It’s easy to imagine an oblivious male reader in the 70s just passing over these scenes as sexually stimulating or what, but reading them as an angry and bereft queer was WILD because it’s all painfully spelled out. Tiptree was raging when they wrote those scenes and it’s obvious.

Listen, zombie. Believe me. What I could tell you—you with your silly hands leak-ing sweat on your growth-stocks portfolio. One-ten lousy hacks of AT&T on twenty-point margin and you think you’re Evel Knievel. AT&T? You doubleknit dummy, how I’d love to show you something.

The Girl Who Was Plugged In (1974)

Look, dead daddy, I’d say. See for instance that rotten girl? In the crowd over there, that one gaping at her gods.

One rotten girl in the city of the future. (That’s what I said.) Watch.

The stories in Her Smoke Rose Up Forever are obsessed with death, stasis of human potential, the disgusting and penetration-obsessed totality of binarized/patriarchal male violence of Empire. Without knowing anything about Tiptree’s life these stories might appear as little more than typical male fantasy space race sci-fi, which I have little tolerance reading. Tiptree was truly lauded as a new heavyweight champion of SFF when “he” debuted, to the point where an earlier edition of this book features an introduction stating that there is no way Tiptree could possibly be female as is rumored because no woman could possibly write stuff of this caliber. Fucking lol guys, wow.

A handful of stories include women and people of color. The women of color appear frequently from empowered environments of the far future and their appearance is simply described for tone (no food adjectives), which I found interesting.

Tiptree was born into a high society Victorian family, who as a child was brought by their questionably abusive mother on literal expeditions ‘into’ Africa (the mother wrote travelogues for Vogue magazine). Tiptree lived as a white woman who struggled with depression and feeling constrained by gender roles despite their environment of affluence, and it wasn’t until they enlisted in an all-female WWII intelligence unit and went on to join the newly formed CIA that they began to feel a sense of agency in their life. There’s loads to say about all that, but the fact that their stories are beset with terrifying and controlling white jocks of upper echelon society is probably a very legit reflection of the environments they operated within.

But the stories, man. They are good. Many are available online, for instance The Women Men Don’t See, The Girl Who Was Plugged In, Houston Houston Do You Read and The Screwfly Solution (notably written not as Tiptree but as Raccoona Sheldon), so get a taste if you’re interested and get the book itself if you want more.

Heavy heavy heavy. Recommended with warnings.