Originally written for cinéSPEAK journal as No Imagination: A Working Class Sci-fi Writer’s Read of Don’t Look Up

**Spoilers Alert**

During the first great plague of the 21st century, Hollywood took to producing Don’t Look Up, an engrossing film about a comet striking the Earth and all of humanity too caught up reacting to their social media feeds to stop it. Yes, it had been a little while since us sci-fi disaster film aficionados had a good ‘comet threatens earth’ jaunt to stoke our imaginations, let alone one made as a satire. In between the global Delta and Omicron pandemic surges, a couple weeks before the anniversary of the January 6th insurrection on this nation’s capitol building, Netflix debuted the film, right in time for Christmas.

There I was, washing dishes in my little market-rate apartment, NPR talking about the movie, keeping me company from the other room. I didn’t pay attention until the host aired a scene: Two scientists have discovered a comet that will 100% strike Earth, and soon. The scientists have an audience with the President of the United States, who appears to listen, and then demands that the details of this certain catastrophic event be downplayed so as not to cause a panic before the coming elections. Wow, I laughed to myself. This movie might actually give us some much-needed commentary on the current state of world affairs. Its not-quite-1984-inspired authoritarian title, instructing us to refrain from the most common of gestures, had me intrigued–was it possible for Hollywood to produce a scathing satire on the dire state of human civilization in an era of social media?

Well, let’s start with this: We have a movie about a global extinction event that only involves Americans. You could say it’s a satire about how people react to life-changing information, but those people are a highly educated, overwhelmingly white,* cis-hetero managerial class of (again) Americans. It’s a disaster movie about a comet, yet there’s even less looming comet footage than Melancholia, Lars von Trier’s 2011 film also about an elite class of (wealthier) white people dealing with their impending death by heavenly impact. In Melancholia, at least, we stay within the estate of its upper class main characters and their isolated wedding reception universe, and there’s none of Don’t Look Up’s manic cutscenes of the apparent whole world to distract us from the fact that this is a movie about the low-stakes problems of two middle class Americans–a subject matter that exhausts this working class writer for its continued lack of imagination (e.g. casting), failure to take narrative risks (e.g. depictions of common people accepting corrupt authority), and frankly, wasting resources in the face of would-be feature length filmmakers out there, if only they could get the funding they deserve.

Don’t Look Up adds to a tiresome Hollywood canon of speculative films set during cataclysms, outer space, and future flung dystopias/utopias, where the leading characters are white and many of the material horrors of our present time are merely projected into future and alternate realities, unchallenged and implied to be natural. New York-born, Philly-based speculative filmmaker and documentarian, M. Asli Dukan put a name to this in her brief and easy-to-follow 2015 video, The White Fantastic Imagination. It is one where stories featuring “futuristic, fantastic, and-or extra-imaginative elements as part of its structure” not only exclude Black people, “but in a sense […] infer that Black people didn’t matter in the past, don’t matter in the present, and will not matter in the future.” It’s a phenomenon in arts and media, originating from “prototypical forms of utopian fiction, fantastic voyages, scientific romances, and lost world/lost race narratives [of the 1500s], within a world beginning to be defined by European imperialism.” In other words, we’re talking about “the ideology of white supremacy in speculative fiction.” Don’t Look Up, after all, is a 21st century American film centering a pair of US government-connected scientists and their individual problems, where all life-saving decisions are made by a cadre of corrupted, resource-hoarding, and weak-willed no imagination having white people.

The movie opens up on Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence), a young white woman, whose conservative lab-appropriate dress contrasts with winged eyeliner, nose piercings, and cherry red hair. She’s crunching astronomical data in the observatory while absentmindedly mouthing the lyrics to 1993’s Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthing Ta F’ Wit (playing flaccidly from her headphones)–when she discovers a comet. In the next scene, we watch her join fellow PhD candidates and their professor, Dr. Randall Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio), a frumpy plaid button-up with khakis type, as they pop bottles celebrating the comet’s discovery, while Chingy’s 2003 hit Right Thurr plays tepidly in the background. When our protagonists subsequently calculate that the comet will smash into Earth in six months and 14 days, they rush to perform their due diligence by informing NASA, only to get hushed up by both the agency’s head and the president and her cabinet. Mindy proceeds to freak out, while Dibiasky shuts down. The authorities aren’t doing what they’re supposed to! And once the pair fumble their opportunity to leak the information to the American press (with Dibiasky becoming the target of sexist memes and Mindy, America’s next ‘astronomer I’d like to fuck’), their lives are taken over by the repercussions of this life-changing information that no one gives a damn about. It seems to be the first time ever something like this has happened to them.

Thankfully, a high-ranking official soon appears to aid them. In the scene where Mindy and Dibiasky dial up the head of NASA, the unqualified presidential donor filling the position, Dr. Calder (Hettienne Park), asks them to hold while she phones Dr. Oglethorpe (Rob Morgan). Dr. Theodore “Call Me Teddy” Oglethorpe slides on screen in his charcoal suit and tie, serving up the well-worn role of a calm and collected Black male military professional and scientist. He is the head of NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office. He is the only governmental authority figure to take our protagonists seriously and join their fight. And he is hardly seen or heard from once he’s served the plot device of being Mindy and Dibiasky’s connection to the upper echelon of the United States government.

After that he’s just the chaperone. Oglethorpe waits around with them to see President Orlean (Meryl Streep). He sits by while the two make television appearances. And apparently the trio bond over the few times he’s moved to speak about which celebrity news he is following through his smartphone. Once Dr. Mindy gets swept up in the thrill of being an Orlean administration talking head for the media, Dr. Oglethorpe switches over to being the voice of reason, calling after Mindy once he’s gone full-blown cad to remind him, “Science tells the truth, Randall.” But if Oglethorpe joins the protagonist duo in their fight, why does he not also receive the same level of character development? We don’t get to see his neurodivergent family, his messy affairs, or whoever he’s dating. We don’t see a lick of how this world’s social media sphere sexualizes, demonizes, or meme-ifies him. We don’t see how his life is affected by the Orlean administration denying the leaked comet info and smearing the trio’s character. We don’t even hear him express any strong emotions. And when he’s arrested, he calmly placates the guns-already-drawn cops so he hopefully doesn’t lose his life for existing while Black. If this movie is a satire on the state of American culture–and it’s a movie with an overt female parody of the openly white supremacist Trump administration (and a shitty one at that, with so many jokes hinging on her having been a sex worker)–why is a cishetero state-aligned male professional at the top of his office the singular open acknowledgement of Black people’s treatment in America?

Like the film’s corny protagonists identifying with 30-year-old rap music (before rap became pop), scanning the skies from the contested Mauna Kea Observatory built on sacred indigenous Hawaiian land, these portrayals are pretty cringe, serving up working class viewers an ensemble cast of seemingly familiar and possibly relatable characters, but none of which seem burdened by debt, housing instability, caretaking, or anything that truly threatens their livelihoods, even as the world ends. Instead the film decides to drive its plot by using the different treatments that DiCaprio’s Dr. Mindy, the representative White Man, receives from society compared to Dibiasky, the White Woman, and Oglethorpe, the Black Man. In the final scene, the looming comet is shaking the entire room. The White Man looks around the dinner table with relish and says, “We really did have everything, didn’t we. I mean, when you think about it.” The White Woman sighs, the Black Man drinks in silence. The operative word in Mindy’s statement is “we.”

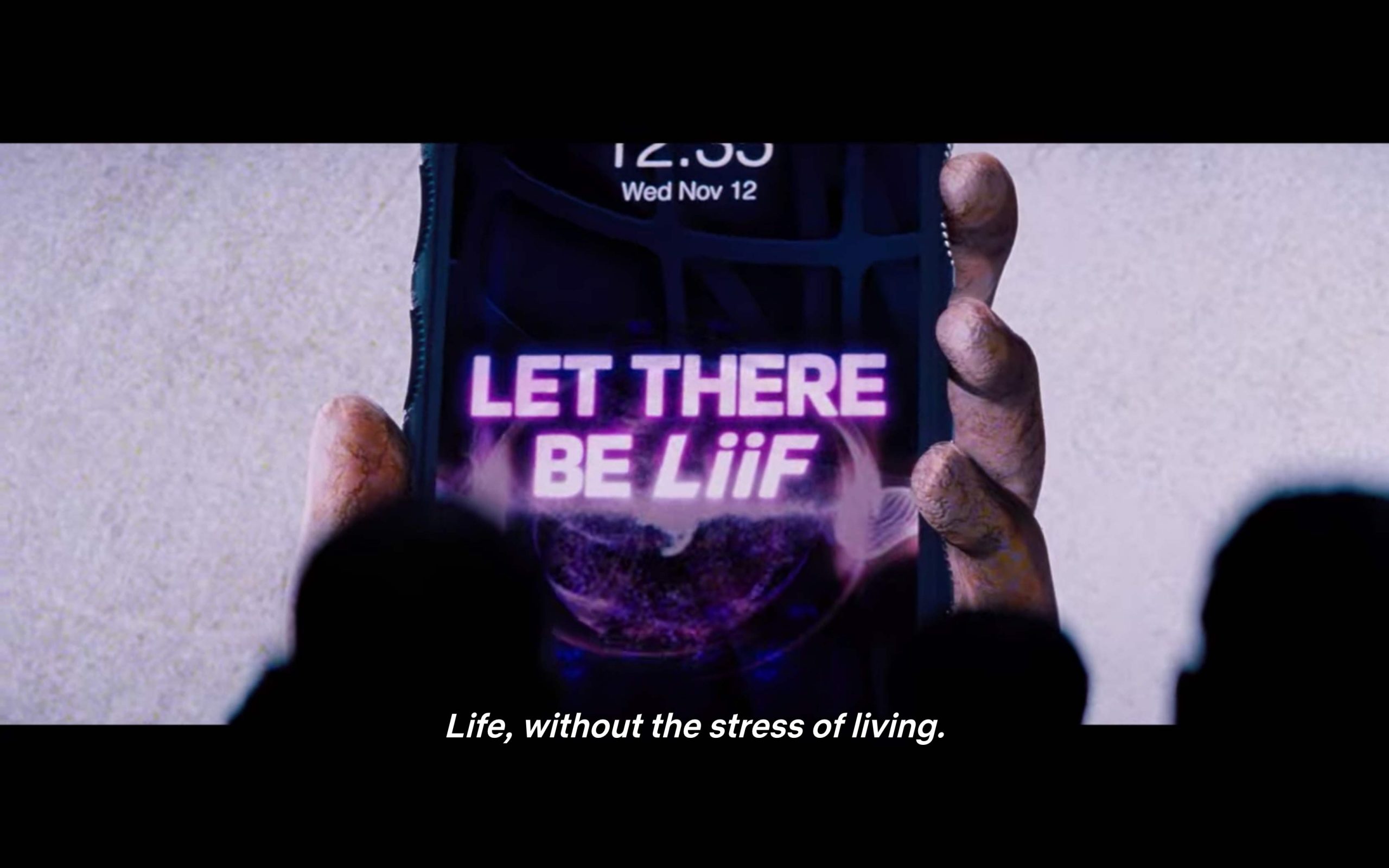

Don’t Look Up is not a poorly made movie. Its plot has consistency, its main characters have arcs, its dystopian details and satirical depictions of pop American society are decadently layered: CERN (inventor of the World Wide Web and Large Hadron Collider experiments for dark matter) is developing precision bomb technology, shovels cost $599.99 due to world-is-ending inflation, and the presidential mission to destroy the comet is called off at the last minute so her genius-man techno-baron superdonor Peter Isherwell (Mark Rylance) can attempt to mine the comet’s precious materials for his BASH brand smartphones. For that matter, watching Don’t Look Up feels like being on social media, because it is shot and cut and interrupted in the same fashion. Many scenes are jumped by cell phones ringing, incoming texts, and incendiary broadcast segments blaring for attention. Even with a central group of lead characters, over the course of the film viewers are exposed to the faces of hundreds of random people and dozens of animals through these editing techniques. We’re hit with montages of riots and demonstrations, familiar political talk show formats and celebrity couple media storms. It’s a world teeming with details, feeding us lots of little bits of interesting information that we can’t quite keep track of or remember fully. It’s a clever way to satirize the fragmented, socially mediated world many Americans find themselves in. In the movie, it even performs the same distracting function, overriding any opportunity for viewers to see its protagonists examine (and not simply react to) the choices they’ve made, while thrusting them back into the plot just in time for them to have a nice family dinner.

Don’t Look Up is just another sad example of Dukan’s White Fantastic Imagination, where no matter how bad things get, “we”–the comfortable whites and acceptable token minorities who support them–can simply choose to get together in a civilized fashion, and all the unaddressed grievances of the past will melt away over wine and small talk and fingerling potatoes. It’s a movie universe where its protagonists don’t admit to themselves what they really want or feel until seconds before the comet strikes, where despite so many cutscenes involving all of supposed life on Earth, its story stays within the scope of Mindy, a naïve and anxious patriarch and the people he fails. And once the plot turns to concerning itself with Mindy and Dibiasky living with the exact date of their once-preventable deaths as they figure out what to do with themselves now that the powers that be have failed and ridiculed and abandoned them, Don’t Look Up’s satirical depictions of American mediated society fall away forgotten as we–working class, exhausted, broke, disabled, and overworked people–are made to sympathize and relate with essentially a pair of managers, who seem to be pretty all right with the dispossession of their very lives by the government. And in 2022, after America’s tumultuous summer 2020 of “racial reckoning,” who is benefitting from this lack of imagination and risk in multimillion dollar storytelling? Don’t be distracted.

*”White” being a mentality well explained in Russell Mean’s speech, For America to Live Europe Must Die.

Where to Watch: Netflix

Don’t Look Up has been nominated in four categories for the 94th Academy Awards–Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, Best Original Score, and Best Film Editing–airing on Sunday March 27, 2022 at 8PM ET on ABC.